A Life in Photographic Art, my second book.

Peter J. Crowley. Some may know him as a photographic artist, father, grandfather and friend. I have seen him as those things, but also as a dreamer, philosopher, anti-authoritarian hippie, (self-described) four-year-old, and my boss. I intern for him multiple afternoons a week. Some days he leaves a note taped to the front door—written on yellow steno pad. Like this one:

That day, I knocked on the door and when I crossed the threshold, I heard the voice of Mick Jaeger waft through the living room. I found PJC at his desk, chuckling to himself about my formality, writing a new blog post and musing about the state of the world.

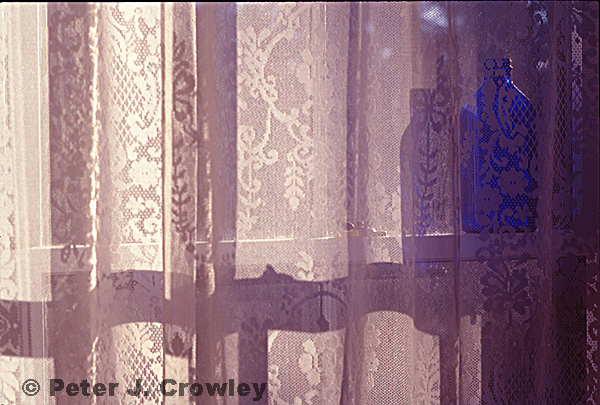

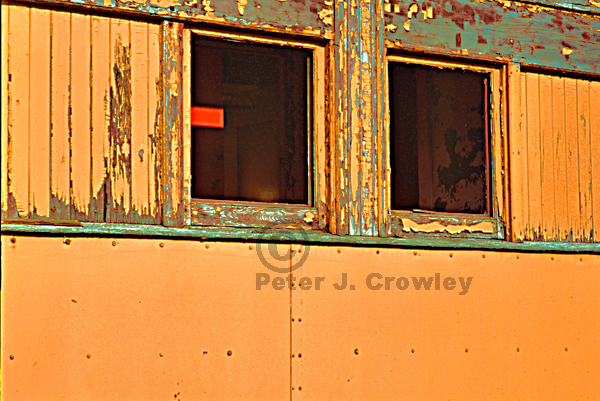

PJC’s apartment living room is bursting with boxes of negatives, slides, and prints, every square inch covered, save for a few pictures of his granddaughter hanging on the wall. From the floor and up the walls are a record of 40 years of a life well lived, photographic art, each image with a life and story of its own.

As I work on cataloguing and organizing the negatives, or searching for a specific print among the boxes we launch into various discussions about artistic integrity, photographic philosophies, and even conspiracy theories. He laments to me about the state of today’s photography world, and his insistence of keeping the integrity and art in photography. His default medium is still black and white film. His camera, the same Nikon 1967 F he’s had for over two decades.

Some days, he sees in light and in shadow and that it’s a good day to go outside and “play.” In other words—forget about work for a while and go take pictures. Sometimes he likes to forget about his age, and live life as if a four-year-old, the same age as his granddaughter. Walking around, he is often of dueling perspectives, seeing light and dark both in the world at large and in his photographs. We stop to take a picture on the side of the road—of an abandoned house, down an alleyway, and of obsolete technology with a free sign. We share our ideas for compositions and try to guess the right settings for our cameras before we check the light meter. It is in actually going out and shooting with PJC that I learn the most, both about how he works and how to improve my own photography.

PJC has as many stories to tell as he has negatives. While we work and photograph, he regales me with tales of musical legends: attending Woodstock, Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie, and The Grateful Dead just to name a few. Earlier today, he spoke of one Grateful Dead concert in the early 1970’s. There were police barricades and a line a mile long. Everyone had to show tickets to the cops to get in. Except for Peter. He bypassed the line, flashed his press pass, waved his three friends in and said, “they’re with me.” He didn’t even have his camera with him. Peter then danced on the grassy football field for nine hours without having to worry about procuring a ticket.

I have been told about how many of Peter’s photographs came to be. For one picture in particular, he told me that he woke up with an idea and had the image in his head for close to three years before finally photographing it. His vision was of pregnant woman, her body and belly cast in warm light and shadow. PJC chuckled a bit when he told me that for years, he asked every pregnant woman he encountered to model for him. A pregnant woman would walk into the restaurant he frequented and his friend would look at her, then at him and say, “Peter, no. Not again,” and he would continue to ask. Eventually, a woman agreed. The photograph was worth the wait, though—it ended up winning an award.

Peter is the habit of writing down everything, from my coming to work that day, to something he wants to email me, to the settings of his camera for every picture he takes, since he claims his memory is shot. In Peter’s sage words, “morphine will screw the memory, but not as much as a pistol,” referring to an incident when he was at the wrong place at the wrong time and had an unfortunate encounter with the mob. Among that life lesson, he has also taught me a few more, both relating to photography and not. I now know that if the government sends me a check, I shouldn’t ask questions. I should go directly to the bank and cash it (and store the cash under my mattress).

Peter J. Crowley is a character among characters. With the slight twinge of an east coast accent, he engages anyone near him with his stories, as his images engage the eye of anyone who sees. Peter’s extensive body of work often makes me wish I had a time machine. To go back and experience the life he portrays in his photographs, from thrilling dramatic performances, to the enchanting movement of dancers, from encounters with cultural icons, to tranquil moments on a New England farm. I could go on to write a dissertation about Peter and his life, lighting, composition, and mood he evokes in his images. I don’t feel I need to, though. Peter’s work, his talent, and stories speak for themselves and I am so grateful to call him my boss.

Do you have any stories about Peter? Comment below, email him or share on Facebook, we would love to hear them! Many will be used through out the book.